There’s been a lot of buzz this week about the promise of a malaria vaccine that is currently in clinical trials across Africa. While the news is encouraging, it will be some time before a vaccine is widely administered to travelers; the most recent vaccine trial has shown a 50% success rate – promising, but not quite the nail in the coffin. For now, malaria prophylactics remain the best line of defense.

In our article on malaria myths and facts, we mentioned some of the misinformation surrounding this disease. Much of the confusion is related to treatment. Hopefully this article will give you an understanding of how malaria treatment works and why it is not the same everywhere around the world.

Different strains of malaria call for different kinds of treatment

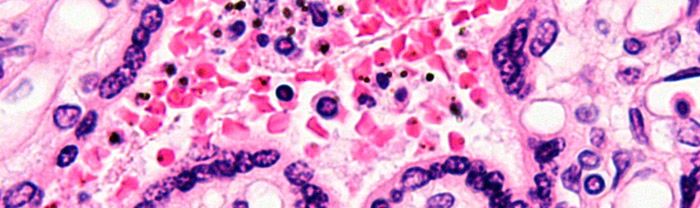

Most people know that malaria is a parasitic disease, but they don’t realize that there are multiple strains. Plasmodium falciparum is the most infamous strain of malaria. It is primarily found in Africa and it is responsible for the greatest number of malaria deaths worldwide.

But there are several other strains, such as plasmodium vivax, which accounts for more than half of the malaria cases in Asia and South America. It is the least deadly strain of malaria, but it is also the most likely to cause relapses (see our malaria myths and facts article for more on relapses).

Plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium vivax are often treated with different medications. But, as you will soon see, strain type is not the only factor.

Treatment depends on the strain, but also the location where you became infected

Plasmodium vivax is often treated with chloroquine. If you came down with p. vivax in Papua New Guinea, however, you would probably receive some combination of quinine sulfate, doxycycline or tetracycline, and primaquine phosphate. That’s because up to 20% of the p. vivax cases in Papua New Guinea have shown resistance to chloroquine. Some strains of malaria have become resistant to typical treatment regimens. As a result, doctors and clinics may prescribe one course of treatment in Indonesia and something completely different in Thailand.

Length and severity of infection are two final factors in determining malaria treatment

Early diagnosis and treatment is critical. If malaria is allowed to persist untreated, serious damage can occur and depending on the strain, death is a real possibility. If malaria is caught early, doctors will often prescribe an oral course of medication. If the infection is not treated quickly, severe malaria can develop, which calls for another level of treatment – often, a regimen of drugs administered intravenously.

Before your next trip

- Consult this country list from the CDC to see which strain of malaria is present at your destination and what prophylactics are recommended.

- Read our thoughts about which malaria prophylactic to take and whether to take them at all.

- Look at this treatment table from the CDC to get a sense for common treatments depending on your destination/strain of malaria found there.

- Have a consultation with a doctor at a travel health clinic several weeks before your trip. After reading all this, you will be able to have an informed discussion with them. They can prescribe prophylactics and further advise you on treatment.

- At your destination, buy an oral course of treatment that you can keep with you as a backup in the event that you come down with symptoms and are unable to access a clinic. I had malaria in rural, northwest Benin and I was very lucky to have coartem (an emergency standby oral course of treatment for p. falciparum) with me.

Have you had malaria before? If so, where did it occur and what kind of treatment did you receive?

{ 4 comments… add one }